Assessing health and environmental impacts of foods

Small changes made by individuals can improve health and the planet

By Dr Michael Clark

28 October 2019

We are faced with numerous health and environmental challenges — obesity , diabetes, climate change, deforestation, biodiversity, pollution, and freshwater scarcity. Although impossible to ignore, it is easy to feel overwhelmed and powerless in the face of these worsening crises, especially as many governments are not taking adequate action to halt them.

The food we choose to eat is a major contributor: two recent systematic analyses found that globally, dietary choices account for nine of the top 15 risk factors for poor health, and are estimated to account for 21-24% of all deaths. Similarly, producing our food is a major contributor to environmental degradation: the source of more than 25% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and the largest cause of deforestation, freshwater use, and biodiversity loss, according to research published in Nature in 2011.

Our latest analysis, published in PNAS, shows that as individuals we can make small changes that will make a difference. Imagine what we could achieve with big changes! My colleagues and I looked at how food consumption affects human and environmental health for multiple indicators and identified which foods are win-wins, as well as those that might be lose-loses.

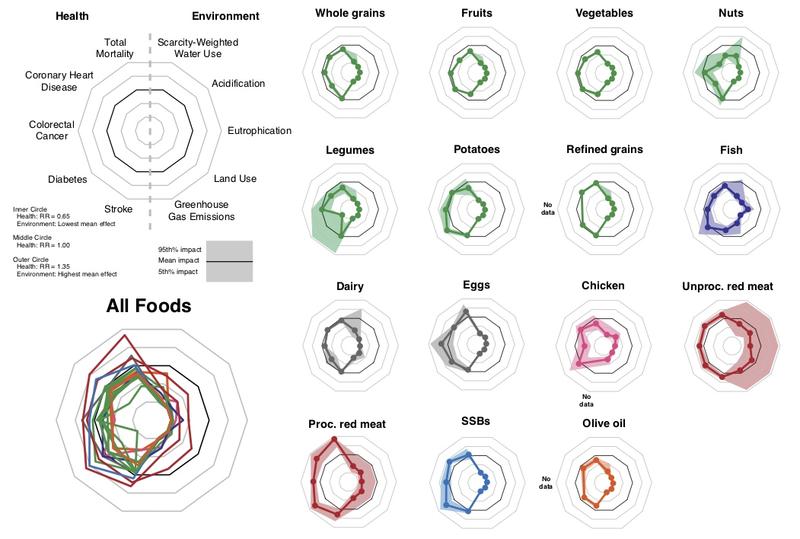

Building diets based on fruits, vegetables, nuts and wholegrains brings improved human health as well as protecting the environment. These foods have low environmental impacts for most indicators, and are associated with decreases in disease risk for multiple health outcomes.

Some foods might be wins for health but loses for environment, and vice versa. Fish consumption, for example, is associated with a reduced risk of disease but also with around 5 to 15 times higher environmental impacts than most plant based foods. In contrast, sugar-sweetened beverages have among the lowest environmental impacts but as many of us are aware, they increase the risk of obesity, leading to higher incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Red and processed red meat are the only foods we identify as clear lose-loses for health and environment. These foods are associated with moderate increases in disease risk for multiple health outcomes, and have much larger environmental impacts than most other foods. Producing a 100g serving of red meat has around five times the environmental impacts of producing a 100g serving of chicken or fish, or a 200g serving of dairy, around 20 times the impact of producing a serving of nuts, legumes or eggs, and around 50 times the environmental impact of producing a serving of whole or refined grain cereals, potatoes, fruits, vegetables, and sugar-sweetened beverages.

This figure from our paper shows how each of the foods is related to the indicators we analysed. The left side of the radar plot shows health outcomes and the right side shows environmental impacts. A food group with low mean impacts for the 10 outcomes would have a small circular radar plot, and one with high impact for the 10 outcomes would have a large circular radar plot.

Diets composed primarily of foods that are win-wins would likely have large health and environmental benefits. For instance, my colleague Marco Springmann led research that estimated that global adoption of a diet that follows recommendations set in the EAT-Lancet Commission would reduce global premature mortality by 18-20% and diet-related greenhouse gas emissions by 54-87%.

Diets are not the only contributor to the current health and environmental challenges. How we produce and process food also matters (as indicated by the shading in the figure), as do environmental and health damages from other sources such as fossil fuel combustion. As consumers, we don’t always have the ability to influence how corporations approach fossil fuel combustion or pollution, but we do have the ability to choose how we eat.

Maintaining current diets and dietary trends is not an option: rates of diabetes and obesity are continuing to increase around the world and environmental targets like those set in the Paris Climate Agreement will become even harder to achieve if we continue to eat the way we currently eat. While we don’t all need to cut out meat altogether, this analysis shows that reducing consumption of the lose-lose foods and increasing consumption of the win-wins can have a positive effect on ourselves and the planet.

Michael Clark is a Postdoctoral Researcher in the Nuffield Department of Primary Health and is part of the LEAP project. His research examines how dietary choices affect environmental sustainability and human health. He uses global models and meta-analyses to examine these issues and to provide insight into what can be done to reduce the impact that diets have on environmental sustainability and human health.